5.4 Papatūānuku

Wāhi Tuarima | Part 5

5.4 Papatūānuku [P]

Papatūānuku is profoundly important in the Ngāi Tahu worldview, as the birthplace of all things of the world, and the place to which they return. Papatūānuku is the wife of Ranginui, and their children are the ancestors of all parts of nature.

This section addresses issues of significance in the takiwā relating to Papatūānuku, the land. An important kaupapa of Ngāi Tahu resource management perspectives and practice is the protection and maintenance of the mauri of Papatūānuku, and the enhancement of mauri where it has been degraded by the actions of humans.

Land use and development activities in the takiwā must be managed in way that works with the land and not against it. Papatūānuku sustains the people, and the people must in turn ensure their actions do not compromise the life supporting capacity of the environment. The cultural, social and economic wellbeing of people and communities is dependent on a healthy and resilient environment.

Ngā Paetae | Objectives

(1) The mauri of land and soil resources is protected mō tātou, ā, mō kā uri ā muri ake nei.

(2) The ancestral and contemporary relationship between Ngāi Tahu and the land is recognised and provided for in land use planning and decision making.

(3) Land use planning and management in the takiwā reflects the principle of Ki Uta Ki Tai.

(4) Rural and urban land use occurs in a manner that is consistent with land capability, the assimilative capacity of catchments and the limits and availability of water resources.

(5) Inappropriate land use practices that have a significant and unacceptable effect on water quality and quantity are discontinued.

(6) Ngāi Tahu has a prominent and influential role in urban planning and development.

(7) Subdivision and development activities implement low impact, innovative and sustainable solutions to water, stormwater, waste and energy issues.

(8) Ngāi Tahu cultural heritage values, including wāhi tapu and other sites of significance, are protected from damage, modification or destruction as a result of land use.

Ngā Take | Issues of Significance

- P1: Papatūānuku

- P2: Intensive rural land use

- P3: Urban planning

- P4: Subdivision and development

- — P4a: Ngāi Tahu S&D guidelines

- P5: Papakāinga

- P6: Stormwater

- P7: Waste Management

- P8: Discharge to land

- P9: Soil conservation

- P10: Contaminated land

- P11: Earthworks

- P12: Vegetation burning and clearance

- P13: Mining and quarying

- P14: Commercial forestry

- P15: Wilding trees

- P16: Transport

- P17: Energy

- P18: Fracking

- P19: Overseas investment

- P20: Tenure review

P1: Papatūānuku

Issue P1: Basic principles of land management, from a Ngāi Tahu perspective.

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

P1.1 To approach land management in the takiwā based on the following basic principles:

(a) Ki Uta Ki Tai;

(b) Mō tātou, ā, mō kā uri ā muri ake nei; and

(c) The need for land use to recognise and provide for natural resource capacity, capability, availability, and limits, the assimilative capacity of catchments.

As a means to:

(a) Protect eco-cultural systems (see Section 5.3 Issue WM6 for an explanation);

(b) Promote catchment based management and a holistic approach to managing resources;

(c) Identify and resolve issues of significance to tāngata whenua, including recognising the relationship between land use and water quality and water quantity;

(d) Provide a sound cultural and ecological basis for assessments of effects of particular activities; and

(e) Recognise and provide for the relationship between healthy land, air and water and cultural well-being.

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

As kaitiaki, Ngāi Tahu have a responsibility for the sustainable use and management of natural resources and the environment. Kaitiakitanga is the basis for tāngata whenua perspectives on land management, and is expressed through a number of key principles, or cultural reference points. The principles enable an approach to land management that recognises the relationships and connections between land, water, biodiversity and the sea (Ki Uta Ki Tai), the need for long term intergenerational thinking (mō tātou, ā, mō kā uri ā muri ake nei), and the importance of working with the land and recognising natural limits and boundaries.

Mō tātou, ā, mō kā uri ā muri ake nei

Thinking ahead with the cultural, economic and social well being of future generations in mind is central to recognising kaitiakitanga objectives. Mō tātou, ā, mō kā uri ā muri ake nei is a tribal whakataukī translated as ‘for us and our children after us’. The policies in this IMP seek to resolve issues of significance by asking the fundamental question: what will the impact of this activity be on those that come after us?

P2: Intensive Rural Land Use

Issue P2: Intensive rural land use is having unacceptable effects on water quality and quantity, biodiversity and soil health, and associated Ngāi Tahu cultural values.

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

P2.1 Rural land use must prioritise the protection of resources and environmental health for future generations. Economic gain must not have priority over the maintenance of the mauri of Papatūānuku, the provider of all things of nature and the world.

P2.2 The adverse effects of intensive rural land use on water, soil and biodiversity resources in the takiwā must be addressed as a matter of priority.

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

The effects of intensive rural land use on water quality, water quantity, indigenous biodiversity and soil health is the key challenge in the takiwā. The lack of regard for local land and water limits has resulted in unacceptable adverse effects on land and water resources. Increased agricultural production on the central plains and in some parts of Te Pātaka o Rākaihautū has come with a high environmental cost; a cost borne largely by tāngata whenua and the wider community. Soil resources are becoming exhausted or depleted in some areas, many waterways are no longer safe to swim or catch fish in, and community groundwater supplies are at risk of nitrate and E.coli contamination.

General policy on the effects of intensive rural land use on freshwater resources is found in Section 5.3 under Issue WM7. Local issues affecting particular catchments are addressed in Part 6.

Land use and development, and Te Pātaka o Rākaihautū

Particular issues of concern for tāngata whenua regarding general land use and development across Te Pātaka o Rākaihautū include:

- Intensification of land use and potential effects on environment and mahinga kai, including increased run off of sediment and contaminants into the bays.

- Coastal land development and potential effects on natural character and cultural landscape values (pressure to exploit outstanding coastal views).

- Limited community wastewater and water supply infrastructure and adverse effects on the environment as a result.

- Granting of subdivision consents despite the lack of appropriate infrastructure in place to support the increased population.

- Protection of known and unknown sites of significance and the settings (cultural landscapes) in which they occur.

- Potential effects of land use and development on indigenous vegetation.

- Loss of access to coastal marine areas.

- Increasing public access to remote and culturally sensitive areas.

P3: Urban and Township Planning

Issue P3: Ngāi Tahu participation in urban and township planning and development.

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

P3.1 To require that local government recognise and provide for the particular interest of Ngāi Tahu Papatipu Rūnanga in urban and township planning.

P3.2 To ensure early, appropriate and effective involvement of Papatipu Rūnanga in the development and implementation of urban and township development plans and strategies, including but not limited to:

(a) Urban development strategies;

(b) Plan changes and Outline Development Plans;

(c) Area plans;

(d) Urban planning guides, including landscape plans, design guides and sustainable building guides;

(e) Integrated catchment management plans (ICMP) for stormwater management;

(f) Infrastructure and community facilities plans, including cemetery reserves; and

(g) Open space and reserves planning.

P3.3To require that the urban development plans and strategies as per Policy P3.2 give effect to the Mahaanui IMP and recognise and provide for the relationship of Ngāi Tahu and their culture and traditions with ancestral land, water and sites by:

(a) Recognising Te Tiriti o Waitangi as the basis for the relationship between Ngāi Tahu and local government;

(b) Recognising and providing for sites and places of importance to tāngata whenua;

(c) Recognising and providing for specific values associated with places, and threats to those values;

(d) Ensuring outcomes reflect Ngāi Tahu values and desired outcomes; and

(e) Supporting and providing for traditional marae based communities to maintain their relationship with ancestral land.

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

Urban development strategies, outline development plans, area plans and other similar planning documents are developed to manage the effects of land use change and development on the environment. It is critical that such initiatives include provisions for the relationship of tāngata whenua with the environment, and that Ngāi Tahu are involved with the preparation and implementation of such plans, as tāngata whenua and as a Treaty partner.

Given the high level status and the influence of some of these documents in urban planning (i.e. they will guide statutory plans and plan changes), it is imperative that Ngā Rūnanga are involved in the early stages of plan development, before public consultation. The ability to address cultural issues and achieve meaningful outcomes is limited when Ngā Rūnanga are invited to comment on draft plans after they have been presented to councillors or the public.

The increased involvement of Ngāi Tahu in urban development processes in the region will result in urban development that is better able to recognise and provide for tāngata whenua values, including affirming connections between Ngāi Tahu culture, identity and place in the urban environment. This is a particularly important issue with regard to the rebuild of Ōtautahi (see Section 6.5 Ihutai).

Cross reference:

» Issue P4: Subdivision and development

P4: Subdivision and Development

Issue P4: Subdivision and development can have significant effects on tāngata whenua values, including sense of place, cultural identity, indigenous biodiversity, mahinga kai, and wāhi tapu and wāhi taonga, but can also present opportunities to enhance those values.

See also P4a: Ngāi Tahu Subdivision and Development Guidelines

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

Processes

P4.1 To work with local authorities to ensure a consistent approach to the identification and consideration of Ngāi Tahu interests in subdivision and development activities, including:

(a) Encouraging developers to engage with Papatipu Rūnanga in the early stages of development planning to identify potential cultural issues; including the preparation of Cultural Impact Assessment reports;

(b) Ensuring engagement with Papatipu Rūnanga at the Plan Change stage, where plan changes are required to enable subdivision;

(c) Requiring that resource consent applications assess actual and potential effects on tāngata whenua values and associations;

(d) Ensuring that effects on tāngata whenua values are avoided, remedied or mitigated using culturally appropriate methods;

(e) Ensuring that subdivision consents are applied for and evaluated alongside associated land use and discharge consents; and

(f) Requiring that ‘add ons’ to existing subdivisions are assessed against the policies in this section.

P4.2 To support the use of the following methods to facilitate engagement with Papatipu Rūnanga where a subdivision, land use or development activity may have actual or potential adverse effects on cultural values and interests:

(a) Site visit and consultative hui;

(b) Cultural Impact Assessment (CIA) reports; and

(c) Tāngata Whenua Advisory Groups.

Basic principles and design guidelines

P4.3 To base tāngata whenua assessments and advice for subdivision and residential land development proposals on a series of principles and guidelines associated with key issues of importance concerning such activities, as per Ngāi Tahu subdivision and development guidelines. Ngāi Tahu Property and residential land developments.

P4.4 To encourage and support Ngāi Tahu Property Ltd, as the tribal property development company, to set the highest possible standard of best practice for residential land developments in the takiwā, consistent with Ngāi Tahu values.

P4.5 To require that Ngāi Tahu Property Ltd engage with Papatipu Rūnanga when planning and developing commercial ventures such as residential property developments, to achieve Policy P4.4.

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

Subdivision and development is an important issue in the takiwā, in both urban and rural settings. Specific issues associated with subdivision and development activities are addressed as a set of Ngāi Tahu Subdivision and Land Development Guidelines (Policy P4.3). The guidelines provide a framework for Papatipu Rūnanga to positively and proactively influence and shape subdivision and development activities, while also enabling council and developers to identify issues of importance and desired outcomes for protecting tāngata whenua interests on the landscape.

While subdivision and residential land development activities can have adverse effects on cultural values, they can also provide cultural benefits, including opportunities to reaffirm connections between tāngata whenua and place. For example, the use of Ngāi Tahu names for developments or roading can re-establish a Ngāi Tahu presence on highly modified urban and rural landscapes. Working to ensure developments have ‘light footprints’ with regard to building design, water, waste and energy also provides cultural benefit and is consistent with achieving the values-based outcomes set out in this IMP.

A cultural landscape approach is used by Papatipu Rūnanga to identify and protect tāngata whenua values and interests from the effects of subdivision, land use change and development. While many specific sites (e.g. pā sites) are protected as recognised historic heritage, the wider contexts, settings or landscapes in which they occur are not. A cultural landscape approach enables a holistic identification and assessment of sites of significance, and other values of importance such as waterways, wetlands and waipuna (see Section 5.8, Issue CL1).

While all proposals for subdivision and development are assessed against the guidelines set out in Policy P4.3, Papatipu Rūnanga identify specific expectations and opportunities associated with residential land developments undertaken by Ngāi Tahu Property the tribal property development company. As other tribal and Rūnanga-based businesses, Papatipu Rūnanga want to see Ngāi Tahu lead the way and set the standard for best practice in all that they do (see Section 4.1, Issue K5).

Many of the catchment sections in Part 6 of this Plan include specific policies to guide subdivision and development in particular areas, to ensure that such activities occur in a manner consistent with protecting local cultural and community values.

"We initially opposed Pegasus due to the sacredness of the site. But it was approved by decision makers, and we ended up working closely with the developers to address cultural issues. They set up a good process that was meaningful, and we ended up with really good outcomes, culturally and environmentally. It was all about attitude - their process was genuine. Many aspects of Pegasus enhance the landscape."

Clare Williams and Joan Burgman, Ngāi Tūāhuriri Rūnanga

Cultural footprints

The effects of development activity on values of importance to Ngāi Tahu is the ‘cultural footprint’ of the development. The cultural footprint is dependent on the nature and extent of values on site, and the wider cultural landscape context within which the development sits. It is also a reflection of the ability of the development to avoid, remedy and mitigate cultural effects, and realise opportunities to provide cultural benefit (e.g. waterways enhancement).

“The cultural significance of the Prestons site is largely a reflection of the associations and relationships of the site with a wider cultural landscape. Thus, for the purposes of cultural impact assessment, the ‘cultural footprint’ of the development extends beyond the physical boundaries of the site.” Cultural Impact Assessment: for a Proposed subdivision and residential development at Prestons Road, Christchurch (2009).

Cross reference:

» General policies in Section 5.8: Cultural landscapes (Issue CL1); Wāhi tapu me wāhi taonga (Issue CL3) and Ngāi Tahu tikanga tūturu (Issue CL7)

Information resources:

» Cultural Impact Assessment for a proposed subdivision and residential development at Prestons Road, Christchurch (2009). Prepared by D. Jolly, on Behalf of Ngāi Tūāhuriri Rūnanga.

» Cultural Impact Assessment Report for Sovereign Palms Residential Development, Kaiapoi. (2010). Prepared by Te Marino Lenihan.

P4a: Ngāi Tahu Subdivision and Development Guidelines

Cultural landscapes

1.1 A cultural landscape approach is the most appropriate means to identify, assess and manage the potential effects of subdivision and development on cultural values and significant sites [refer Section 5.8 Issue CL1].

1.2 Subdivision and development that may impact on sites of significance is subject Ngāi Tahu policy on Wāhi tapu me wāhi taonga and Silent Files (Section 5.8, Issues CL3 and CL4).

1.3 Subdivision and development can provide opportunities to recognise Ngāi Tahu culture, history and identity associated with specific places, and affirm connections between tāngata whenua and place, including but not limited to:

(i) Protecting and enhancing sites of cultural value, including waterways;

(ii) Using traditional Ngāi Tahu names for street and neighborhood names, or name for developments;

(iii) Use of indigenous species as street trees, in open space and reserves;

(iv) Landscaping design that reflects cultural perspectives, ideas and materials;

(v) Inclusion of interpretation materials, communicating the history and significance of places, resources and names to tāngata whenua; and

(vi) Use of tāngata whenua inspired and designed artwork and structures.

Stormwater

2.1 All new developments must have on-site solutions to stormwater management (i.e.zero stormwater discharge off site), based on a multi-tiered approach to stormwater management that utilises the natural ability of Papatūānuku to filter and cleanse stormwater and avoids the discharge of contaminated stormwater to water [refer to Section 5.4, Policy P6.1].

2.2 Stormwater swales, wetlands and retention basins are appropriate land based stormwater management options. These must be planted with native species (not left as grass) that are appropriate to the specific use, recognising the ability of particular species to absorb water and filter waste.

2.3 Stormwater management systems can be designed to provide for multiple uses. For example, stormwater management infrastructure as part of an open space network can provide amenity values, recreation, habitat for species that were once present on the site, and customary use.

2.4 Appropriate and effective measures must be identified and implemented to manage stormwater run off during the construction phase, given the high sediment loads that stormwater may carry as a result of vegetation clearance and bare land.

2.5 Councils should require the upgrade and integration of existing stormwater discharges as part of stormwater management on land rezoned for development.

2.6 Developers should strive to enhance existing water quality standards in the catchment downstream of developments, through improved stormwater management.

Earthworks

3.1 Earthworks associated with subdivision and development are subject to the general policy on Earthworks (Section 5.4 Issue P11) and Wāhi tapu me wāhi taonga (Section 5.8, Issue CL3), including the specific methods used in high and low risk scenarios for accidental finds and damage to sites of significance.

3.2 The area of land cleared and left bare at any time during development should be kept to a minimum to reduce erosion, minimise stormwater run off and protect waterways from sedimentation.

3.3 Earthworks should not modify or damage beds and margins of waterways, except where such activity is for the purpose of naturalisation or enhancement.

3.4 Excess soil from sites should be used as much as possible on site, as opposed to moving it off site. Excess soil can be used to create relief in reserves or buffer zones.

Water supply and use

4.1 New developments should incorporate measures to minimise pressure on existing water resources, community water supplies and infrastructure, including incentives or requirements for:

(i) low water use appliances and low flush toilets;

(ii) grey water recycling; and

(iii) rainwater collection.

4.2 Where residential land development is proposed for an area with existing community water supply or infrastructure, the existing supply or infrastructure must be proven to be able to accommodate the increased population prior to the granting of subdivision consent.

4.3 Developments must recognise, and work to, existing limits on water supply. For example, where water supply is an issue, all new dwellings should be required to install rainwater collection systems.

Water treatment and disposal

5.1 Developments should implement measures to reduce the volume of waste created within the development, including but not limited incentives or requirements for:

(i) Low water use appliances and low flush toilets;

(ii) Grey water recycling; and

(iii) Recycling and composting opportunities (e.g. supporting zero waste principles).

5.2 Where a development is proposed for an area with existing wastewater infrastructure, the infrastructure must be proven to be able to accommodate the increased population prior to the granting of the subdivision consent.

5.3 New rural residential or lifestyle block developments should connect to a reticulated sewage network if available.

5.4 Where new wastewater infrastructure is required for a development:

(i) The preference is for community reticulated systems with local treatment and land based discharge rather than individual septic tanks; and

(ii) Where individual septic tanks are used, the preference is a wastewater treatment system rather than septic tanks.

Design Guidelines

6.1 New developments should incorporate low impact urban design and sustainability options to reduce the development footprint on existing infrastructure and the environment, including sustainable housing design and low impact and self sufficient solutions for water, waste, energy such as:

(i) Position of houses to maximise passive solar gain;

(ii) Rainwater collection and greywater recycling

(iii) Low energy and water use appliances;

(iv) Insulation and double glazing; and

(v) Use of solar energy generation for hot water.6.2 Developers should provide incentives for homeowners to adopt sustainability and self sufficient solutions as per 6.1 above.

6.3 Urban and landscape design should encourage and support a sense of community within developments, including the position of houses, appropriately designed fencing, sufficient open spaces, and provisions for community gardens.

6.4 Show homes within residential land developments can be used to showcase solar hot water, greywater recycling and other sustainability options, and raise the profile of low impact urban design options

Landscaping and open space

7.1 Sufficient open space is essential to community and cultural well being, and the realization of indigenous biodiversity objectives, and effective stormwater management.

7.2 Indigenous biodiversity objectives should be incorporated into development plans, consistent with the restoration and enhancement of indigenous biodiversity on the landscape.

7.3 Indigenous biodiversity objectives to include provisions to use indigenous species for:

(i) street trees;

(ii) open space and reserves;

(iii) native ground cover species for swales;

(iv) stormwater management network; and

(v) home gardens.

7.4 Indigenous species used in planting and landscaping should be appropriate to the local environment, and where possible from locally sourced seed supplies.

7.5 Options and opportunities to incorporate cultural and/or mahinga kai themed gardens in open and reserve space can be considered in development planning (e.g. pā harakeke as a source of weaving materials; reserves planted with tree species such as mātai, kahikatea and tōtara could be established with the long term view of having mature trees available for customary use).

7.6 Developers should offer incentives for homeowners to use native species in gardens, including the provision of lists of recommended plants to avoid, discounts at local nursery, and landscaping ideas using native species.

Cultural footprints

The effects of development activity on values of importance to Ngāi Tahu is the ‘cultural footprint’ of the development. The cultural footprint is dependent on the nature and extent of values on site, and the wider cultural landscape context within which the development sits. It is also a reflection of the ability of the development to avoid, remedy and mitigate cultural effects, and realise opportunities to provide cultural benefit (e.g. waterways enhancement).

“The cultural significance of the Prestons site is largely a reflection of the associations and relationships of the site with a wider cultural landscape. Thus, for the purposes of cultural impact assessment, the ‘cultural footprint’ of the development extends beyond the physical boundaries of the site.” – Cultural Impact Assessment: for a Proposed subdivision and residential development at Prestons Road, Christchurch (2009).

P5: Papakāinga

Issue P5: The right to residence, use and development of ancestral land is inhibited by:

(a) Land zoning rules;

(b) Housing density rules;

(c) Provision of infrastructure and services;

(d) Multiple ownership; and

(e) Lack of council recognition of paper roads and easements as access points to Māori land.

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

P5.1 To recognise that are a number of issues and barriers associated with the use and development of ancestral and Māori reserve land for the purposes for which it was set aside, and that these may vary between different hapū/Papatipu Rūnanga.

P5.2 To require that local and central government recognise that the following activities, when undertaken by tāngata whenua, are appropriate when they occur on their ancestral land in a manner that supports and enhances their ongoing relationship and culture and traditions with that land:

(a) Papakāinga;

(b) Marae; and

(c) Ancillary activities associated with the above.

P5.3 To require that the city and district plans recognise and provide for papakāinga and marae, and activities associated with these through establishing explicit objectives, policies and implementation methods, including:

(a) Objectives that specifically identify the importance of papakāinga development to the relationship of Ngāi Tahu and their culture and traditions to ancestral land; and

(b) Zoning and housing density policies and rules that are specific to enabling papakāinga and mixed use development; and that avoid unduly limiting the establishment of papakāinga developments through obligations to avoid, remedy or mitigate adverse effects on the environment.

P5.5 To require that the district plans and land titles clearly recognise the original paper roads that provided access to Māori land.

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

Papakāinga, marae and associated ancillary activities located on ancestral land are important to enable tāngata whenua to occupy and use ancestral land in a manner that provides for their ongoing relationship with this land, and for their social, cultural and economic well-being.

A key issue associated with papakāinga is that such development is not easily provided for within existing planning and policy frameworks. Existing legal land controls such as zoning and housing density rules can be a barrier, as papakāinga developments may require smaller lot sizes or higher density housing than allowed in particular zones. Multiple ownership of Māori land is another significant barrier to the ability of whānau and hapū to live on ancestral land (see Case Study: Rāpaki Reserve, Multiple Ownership and Tūrangawaewae).

The purpose of this policy is to enable use and develop ancestral land consistent with the purposes for which it was designated, without the need for expensive subdivisions and the risk of further land loss. Māori land (freehold and reserve lands) was intended to provide an economic base for Ngāi Tahu living in particular areas.

CASE STUDY: Rāpaki Reserve, Multiple ownership and Tūrangawaewae

The Rāpaki Reserve was set aside for Rāpaki Ngāi Tahu as part of the Port Cooper Purchase signed between Ngāi Tahu and the Crown in 1859. The reserve is a good example of the difficulties experienced with multiple ownership and the development of Māori land.

When Māori Land was originally owned by more than one person, then each of those persons could bequeath his/her interest to successors who, in turn, could do the same. Over time, the number of owners has increased exponentially to the point where there are so many owners that it is difficult to get agreement to do anything at all with the land.

Further, because of the inadequacy of their land reserves, Ngāi Tahu were forced to leave their settlements and now these owners are scattered all around New Zealand and other countries, making a representative meeting next to impossible to organise. With the passage of time and the increase in population, the inadequacy of the reserve land

to provide for the people becomes more and more oppressive.

The result is that in many cases it is extremely difficult for anyone to make any use of Māori Reserved land. With each generation that passes, the number of owners increases still further, and the challenge of putting the land to some constructive use becomes more and more difficult and, in many cases, impossible. On one hand, multiple ownership

has protected our land from being sold off, but on the other hand we can’t do anything with it.

It is important that local government understand that Ngāi Tahu never wanted multiple ownership. For Ngāi Tahu ownership consisted of a complex series of rights which were recognised by other whānau, hapu, and iwi. The rights themselves could vary from place to place, but in all cases were recognised by those concerned.

The Crown imposed multiple ownership on us. For this reason, it is up to the Crown or its delegated representatives (regional and territorial authorities) to help us resolve this problem.

In today’s planning environment, district zoning and housing density rules are often a barrier to the use and development of Māori land for the purpose it was designated for. However, the Rāpaki case is more complex. Rāpaki reserve land was originally reserved for habitation and council zoning reflected that purpose by creating a residential zone. However, despite a zoning which recognised the purposes of the reserve, few houses have been built on the reserve land because there are so many owners that agreement to sell any part of the reserve to an individual cannot be reached. Rāpaki whānau cannot afford to go through lengthy planning and legal processes to subdivide land. Every owner has a say on how the land is used and the processes for recognising that right are lengthy and costly.

The Ru Whenua ki Otautahi created an urgency to address these issues. Some Rāpaki whānau living on the west side of the marae have lost their homes and land. These whānau have already been through the complexities and expense of changing multiple owned sections into private land for housing, in order to live where they have been living. They want to re-build at Rāpaki, but are once again faced with the same issue. We need to find a way to enable our people to live on their turangawaewae; their ancestral land. Why should our kaumatua who have now lost their home be forced to live the rest of their days away from Rāpaki?

Source: Te Whakatau Kaupapa 1990 pages 5–30 to 5-32, and discussions with June Swindells (Rāpaki Rūnanga)

P6: Stormwater

Issue P6: The discharge of stormwater in urban, commercial, industrial and rural environments and can have effects on water quality.

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

P6.1 To require on-site solutions to stormwater management in all new urban, commercial, industrial and rural developments (zero stormwater discharge off site) based on a multi tiered approach to stormwater management:

(a) Education - engaging greater general public awareness of stormwater and its interaction with the natural environment, encouraging them to take steps to protect their local environment and perhaps re-use stormwater where appropriate;

(b) Reducing volume entering system - implementing measures that reduce the volume of stormwater requiring treatment (e.g. rainwater collection tanks);

(c) Reduce contaminants and sediments entering system - maximising opportunities to reduce contaminants entering stormwater e.g. oil collection pits in carparks, education of residents, treat the water, methods to improve quality; and

(d) Discharge to land based methods, including swales, stormwater basins, retention basins, and constructed wetponds and wetlands (environmental infrastructure), using appropriate native plant species, recognising the ability of particular species to absorb water and filter waste.

P6.2 To oppose the use of existing natural waterways and wetlands, and drains, for the treatment and discharge of stormwater in both urban and rural environments.

P6.3 Stormwater should not enter the wastewater reticulation system in existing urban environments.

P6.4 To require that the incremental and cumulative effects of stormwater discharge are recognised and provided for in local authority planning and assessments.

P6.5 To encourage the design of stormwater management systems in urban and semi urban environments to provide for multiple uses: for example, stormwater management infrastructure as part of an open space network that provides for recreation, habitat and customary use values.

P6.6 To support integrated catchment management plans (ICMP) as a tool to manage stormwater and the effects of land use change and development on the environment and tāngata whenua values, when these plans are consistent with Policies P6.1 to P6.4.

P6.7 To oppose the use of global consents for stormwater discharges.

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

Stormwater run off from urban, industrial and rural environments can have significant effects on water quality and waterway health. Improving stormwater management requires on site, land-based solutions to stormwater disposal, alongside initiatives to reduce the presence of sediments and contaminants in stormwater, and reducing the volume of stormwater requiring treatment. Low impact development and low impact urban design are fundamental features of sustainable stormwater management. Aligning stormwater treatment and disposal with best practice methods will have an overall benefit to water quality

"Just because a waterway is degraded does not mean it is OK to use it for the disposal and treatment of stormwater."

IMP Working Group, 2012

Cross reference:

» Issue P4: Subdivision and development

» Section 5.6, Issue WH6: Subdivision and coastal development – Whakaraupō

P7: Waste Management

Issue P7: There are specific cultural issues associated with the disposal and management of waste.

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

P7.1 To require that local authorities recognise that there are particular cultural (tikanga) issues associate with the disposal and management of waste, in particular:

(a) The use of water as a receiving environment for waste (i.e. dilution to pollution); and

(b) Maintaining a separation between waste and food.

P7.2 To actively work with local government to ensure that waste management practices protect cultural values such as mahinga kai and wāhi tapu and are consistent with Ngāi Tahu tikanga

P7.3 To require waste minimisation as a basic principle of, and approach to, waste management. This means reducing the volume of waste entering the system through measures such as:

(a) Education about wise water use;

(b) Composting and recycling programmes;

(c) Incentives for existing and new homes, business, developments and council services to adopt greywater recycling and install low water use appliances; and

(d) On site solutions to stormwater that avoid stormwater entering the wastewater system.

P7.4 To continue to oppose the use of waterways and the ocean as a receiving environment for waste

P7.5 To require alternatives to using water as a medium for waste treatment and discharge, including but not limited to:

(a) Using waste to generate electricity;

(b) Treated effluent to forestry; and

(c) Treated effluent to non food crop.

P7.6 To require higher treatment levels for wastewater: ‘we should not have to rely on mixing and dilution of wastewater to mitigate effects’.

P7.7 To work towards achieving zero waste at our marae, through the reduction of waste produced, and the use of composting and recycling programs.

P7.8 To oppose the use of global consents for activities associated with management and discharge of wastewater.

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

Waste management and disposal is an issue in the region whereby tāngata whenua often have distinctive cultural perspectives that differ from those of the wider community. The most obvious example is the use of water to treat (dilute) and discharge waste. The practice of discharging sewage into waterways and the marine environment is highly offensive for tāngata whenua, as these areas are, or are connected to, mahinga kai or food gathering areas.

While the discharge of treated sewage or other wastewater may be within acceptable biological or physical standards, it is not acceptable from a cultural perspective. Water that contains waste is seen as degraded, even if the waste is treated. If water contains waste then it cannot be used to harvest mahinga kai. These basic policies are underpinned by a sound environmental and ecological understanding of the need to protect water and food supplies.

The separation between kai (food) and human waste streams is also an issue with regard to the management of ‘bio-solids’ (a by-product of the sewage treatment process). While tāngata whenua may support the disposal of biosolids onto forestry plantations, the use of biosolids on food crops would be culturally unacceptable.

Tāngata whenua have continuously and strongly advocated for discharge to land as a waste management tool in the region, utilising the natural ability of Papatūānuku to filter and cleanse wastewater. For example, the use of constructed wetlands to treat stormwater or sewage capitalizes on the natural ability of wetlands as the ‘kidneys’ of the land.

Waste minimisation as an approach to waste management is consistent with protecting cultural values and achieving outcomes set out in this IMP. Reducing the volume of solid waste and wastewater produced in the takiwā will reduce pressure on existing infrastructure, and on the environment and cultural values.

"The absence of information about potential adverse effects does not mean that there is no effect (e.g. with reference to effects of endocrine disrupters in treated sewage discharged to the Whakaraupō)."

Rāpaki IMP hui, 2010

"The key issue is: when people use water, where and how do they return it?"

Robin Wybrow, Wairewa Rūnanga

Tiaki Para: A Study of Ngāi Tahu Values and Issues Regarding Waste

Tiaki Para was a collaborative research project that examined Ngāi Tahu traditional and contemporary views and cultural practices associated with waste management. The objectives of the study were to investigate cultural values within a sustainable waste management framework, identify Ngāi Tahu preferences regarding waste treatment and disposal, and to provide culturally based recommendations for future waste management.

A number of key themes emerged from the Tiaki Para study:

- Ngāi Tahu have established cultural traditions and associated cultural practices in relation to managing different types of wastes, particularly those associated with the human body;

- These traditions continue to play a role in contemporary life and influence the way Ngāi Tahu respond to waste management issues;

- Ngāi Tahu issues and values associated with waste and waste management are consistent and specific with regard to maintaining the separation between food chain and human waste streams and utilising natural services (e.g. using land or constructed wetlands as a medium); and

- Ngāi Tahu are solution focused, pragmatic and open to alternatives for sustainable waste management, but are limited in their ability to influence current waste management paradigms.

Source: Pauling, C. and Ataria, J. 2010. Tiaki Para: A Study of Ngāi Tahu Values and Issues Regarding Waste. Manaaki Whenua Press, Landcare Research, Lincoln.

Cross reference:

» Issue P8: Discharge to land

» General policy on water quality (Section 5.3, Issue WM6)

» General policy on coastal water quality (Section 5.6, Issue TAN2)

» Section 6.4 (Waimakariri), Issue WAI1

» Section 6.5 (Ihutai), Issue IH4

» Section 6.8 (Akaroa), Issue A1

» Section 6.6 (Whakaraupō), Issue WH1

P8: Discharge to Land

Issue P8: Discharge to land can utilise the natural abilities of Papatūānuku to cleanse and filter contaminants, but must still be managed to avoid adverse effects on soil and water resources.

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

P8.1 To require that discharge to land activities in the takiwā:

(a) Are appropriate to the soil type and slope, and the assimilative capacity of the land on which the discharge activity occurs;

(b) Avoid over-saturation and therefore the contamination of soil, and/or run off and leaching; and

(c) Are accompanied by regular testing and monitoring of one or all of the following: soil, foliage, groundwater and surface water in the area.

P8.2 In the event that that accumulation of contaminants in the soil is such that the mauri of the soil resource is compromised, then the discharge activity must change or cease as a matter of priority.

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

Discharges to land can include treated sewage (e.g. biosolids and wastewater), stormwater, domestic wastewater, industrial wastewater, or farm effluent. Tāngata whenua have always supported discharge to land as an alternative to discharge to water, given the natural ability of Papatūānuku to cleanse and filter contaminants from waste. However support for discharge to land is provisional on appropriate management of the activity. Over-saturation and overburdening of soils with wastewater, effluent or other discharge compromises the mauri of the land (Issue P9 Soil Conservation) and can result in run off or seepage into groundwater and waterways in the area.

Cross reference:

» Issue P9: Soil conservation

P9: Soil Conservation

Issue P9: The mauri of the soil resources of the takiwā can be compromised by inappropriate land use and development.

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

P9.1 To sustain and safeguard the life supporting capacity of soils, mō tātou, ā, mō kā uri ā muri ake nei.

P9.2 To require the appropriate valuation of soil resources as taonga and as natural capital, providing essential ecosystem services.

P9.3 To protect the land from induced soil erosion as a result of unsustainable land use and development.

P9.4 To support the following methods and measures to maintain or improve soil organic matter and soil nutrient balance, and prevent soil erosion and soil contamination:

(a) Matching land use with land capability (i.e. soil type; slope, elevation);

(b) Organic farming and growing methods;

(c) Regular soil and foliage testing on farms, to manage fertiliser and effluent application levels and rates;

(d) Stock management that avoids overgrazing and retires sensitive areas;

(e) Restoration and enhancement of riparian areas, to reduce erosion and therefore sedimentation of waterways;

(f) Restoration of indigenous vegetation, including the use of indigenous tree plantations as erosion control and indigenous species in shelter belts; and

(g) Avoiding leaving large areas of land/soil bare during earthworks and construction activities.

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

Soil is a fundamental resource, and together with air and water, is the basis on which life depends. As the natural capital upon which much of the region’s economy depends, it is critical that the true (and non replaceable) value of our soils is recognised and provided for in policy and planning processes.

Land use, subdivision and development activities must have appropriate controls to avoid over-saturation, contamination and erosion of soils. For example, in the Whakaraupō catchment (Section 6.6), historical deforestation, inappropriate land use practices and urban development have destabilized vulnerable soils and accelerated erosion of the highly erodible Port Hills soils, and catchment erosion is a significant external source of sediment to the harbour.

An important feature of soil conservation is the promotion of activities that contribute to the protection and enhancement of the soil resource. This includes the incorporation of indigenous biodiversity into urban and rural landscapes, and soil and foliage testing on farms.

Natural capital

For farming to remain viable, the physical environment in which it is based needs to be sustained in a healthy condition. This is because farming is dependent on “natural capital” – the stocks of natural resources such as water, soil and biodiversity – and the “services” that this natural capital provides. These services include clean air and water, the creation and maintenance of fertile soils, pollination, livable climates, raw materials, genetic resources for growing food and fibre, and processes to decompose and assimilate waste. Although these

services are often taken for granted, they have immense value. Many are indeed priceless, as they have no known substitutes.

Source: Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment 2004

Cross reference:

» Issue P1: Papatūānuku

» Issue P8: Discharge to land

» Issue P10: Contaminated land

» Section 6.6 (Whakaraupō), Issue WH4

P10: Contaminated Land

Issue P10: Ngāi Tahu must be involved in decision making about contaminated land.

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

P10.1 The management of contaminated land must recognise and provide for specific cultural issues, including:

(a) The location of contaminated sites;

(b) The nature of the contamination;

(c) The potential for leaching and run-off;

(d) Proposed land use changes; and

(e) Proposed remediation or mitigation work.

P10.2 To require appropriate and meaningful information sharing between management agencies and tāngata whenua on issues associated with contaminated sites.

P10.3 To require investigation and monitoring of closed landfill sites to determine:

(a) Whether the site is a contaminated site; and

(b) The level of environmental risk to groundwater and soil from leaching of contaminants.

P10.4 To require that remedial work is undertaken at closed landfill sites where leaching of contaminants is occurring, to prevent contamination of groundwater, waterways, and coastal waters.

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

Contaminated land can have adverse effects on the environment, including the potential for contaminants to leach into groundwater. Contaminated land can also have effects on Ngāi Tahu cultural associations. Contaminated sites or areas may be on, near or adjacent to land with mahinga kai, wāhi tapu or historical associations. For example, an historical landfill at Takapūneke near Akaroa is identified as an issue of particular significance in that region (see Section 6.8, Issue A6). Tāngata whenua need to be aware of the locations and extent of contaminated land in their takiwā, and be involved in decision making about these sites.

Cross reference:

» Section 6.8 (Akaroa), Issue A6

P11: Earthworks

Issue P11: Earthworks associated with land use and development need to be managed to avoid damaging or destroying sites of significance, and to avoid or minimise erosion and sedimentation.

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

P11.1 To assess proposals for earthworks with particular regard to:

(a) Potential effects on wāhi tapu and wāhi taonga, known and unknown;

(b) Potential effects on waterways, wetlands and waipuna;

(c) Potential effects on indigenous biodiversity;

(d) Potential effects on natural landforms and features, including ridge lines;

(e) Proposed erosion and sediment control measures; and

(f) Rehabilitation and remediation plans following earthworks.

Risk of damage of modification to sites of significance

P11.2 To require that tāngata whenua are able to identify particular areas whereby earthworks activities are classified a restricted discretionary activity, with Ngāi Tahu values as a matter of discretion.

P11.3To use to the methods identified in Section 5.8 Policy CL4.6 (Wāhi tapu me wāhi taonga) where an earthworks activity is identified by tāngata whenua as having actual or potential adverse effects on known or unknown sites of significance.

P11.4 To advocate that councils and consent applicants recognise the statutory role of the Historic Places Trust and their legal obligations under the Historic Places Act 1993 where there is any potential to damage, modify or destroy an archaeological site.

P11.5 To require that the Historic Places Trust (HPT) and local authorities recognise and provide for the ability of tāngata whenua to identify wāhi taonga and wāhi tapu that must be protected from development, and thereby ensure that an Authority to damage, destroy or modify a site is not granted.

P11.6 To avoid damage or modification to wāhi tapu or other sites of significance as opposed to remedy or mitigate.

Indigenous vegetation

P11.7 To require that indigenous vegetation that is removed or damaged as a result of earthworks activity is replaced.

P11.8 To require the planting of indigenous vegetation as an appropriate mitigation measure for adverse impacts that may be associated earthworks activity. Erosion and sediment control

P11.9 To require stringent and enforceable controls on land use and earthworks activities as part of the resource consent process, to protect waterways and waterbodies from sedimentation, including but not limited to:

(a) The use of buffer zones;

(b) Minimising the extent of land cleared and left bare at any given time; and

(c) Capture of run-off, and sediment control.

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

The term ‘earthworks’ is used to describe activities that involve soil disturbance, land modification and excavation and can occur at a range of scales from individual house sites (e.g. installation of septic tanks and landscaping) to large residential subdivisions or regional infrastructure. Of particular importance is earthworks in the beds and margins of waterways (see Section 5.3, Issue WM12).

Any activity that involves ground disturbance has the potential to uncover cultural material or wāhi tapu. Activities such as subdivision and land use change can increase the sensitivity of a site with regard to effects on sites of significance. Ngāi Tahu use a number of mechanisms to manage the risk to wāhi tapu and wāhi taonga as a result of earthworks. The appropriate protection mechanism reflects whether the site or area is considered low or high risk for the potential for accidental finds or damage, destruction of modification of known or unknown cultural and historic heritage sites (see Section 5.8, Issue CL3 Wāhi tapu me wāhi taonga).

Erosion and sediment control is also a key issue of concern with regard to earthworks. Activities such as residential land development can leave large areas of land cleared with bare soil exposed, increasing the risk of erosion and the discharge of sediment into waterways, harbours or the sea.

Cross reference:

» General policy on wāhi tapu me wāhi taonga (Section 5.8 Issue CL3)

» Issue P4: Subdivision and development

» Issue P6: Stormwater.

» Issue P13 Mining and quarrying

P12: Vegetation Burning and Clearance

Issue P12: Vegetation clearance can contribute to:

- Continued fragmentation and loss of remnant native bush and habitat, particularly along streams and gullies;

- Soil erosion and increased sedimentation into waterways and coastal waters;

- Changes to the water holding capacity of the catchment (i.e. stormwater runs off rather than absorbs);

- Loss of opportunities for regeneration;

- Loss of nutrients and carbon from the soil; and

- Change in landscape and natural character.

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

P12.1 To promote land use and land use management that avoids undue soil disturbance and vegetation clearance

P12.2 To oppose vegetation clearance in the following areas:

(a) Areas identified as high risk for soil erosion;

(b) Areas identified as significant for protection of indigenous biodiversity; and

(c) Areas identified as culturally significant.

P12.3 To require that clearing of riparian vegetation along waterways, wetlands, lakes or waipuna is prohibited in the takiwā.

P12.4 To oppose the designation of kānuka, mānuka and pātōtara as ‘scrub’, and therefore the clearance of these culturally and ecologically significant species

P12.5 To require the use of appropriately sized and generous buffers to protect waterways from the vegetation clearance activities.

P12.6 To assess consent applications for vegetation burning or clearance with reference to the following criteria:

(a) Location of the activity:

- What is the general sensitivity of the site to the proposed activity?

- What is the slope of the land? Is the site at risk of erosion?

- What is the proximity to remnant native bush or restoration sites?

- What waterways, wetlands or waipuna exist on the site?

- What is the value of the site as a habitat?

- What are the dominant species on the site, and what is the percentage of indigenous vs non indigenous species?

- Are there specific cultural values or cultural landscape features in the area that may be affected?

(b) Land use:

- What is the land use that the clearance is enabling, is it existing or new?

- How well does the proposed activity ‘fit’ with the existing landscape?

- Is the proposed land sustainable?

- Avoiding and mitigating adverse effects?

- What provisions are in place to address sediment and erosion control, and the protection of waterways?

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

Vegetation is cleared and burned for land management purposes, often as a means to convert land from one use to another. In the Canterbury high country and the hill country of Te Pātaka o Rākaihautū, vegetation clearance and burning is often associated with the creation or maintenance of pasture. A cultural issue associated with this activity is that the clearing of ‘scrub’ for pasture often includes indigenous species such as kānuka, mānuka and pātōtara (mingimingi). Kānuka (Kunzia ericoides) and mānuka (Leptospermum sco parium) and pātōtara (Leucopogon fraseri) are taonga species under the NTCSA 1998 (Schedule 97). Kānuka and mānuka are good nursery species for other indigenous species.

Vegetation clearance also occurs as part of subdivision and residential land development activities. Often large areas of land are cleared and left bare for a long period of time during the construction phase. This increases the risk of erosion and also sedimentation into waterways.

"Long term State of the Environment reporting through the Land Cover data base has shown that overall, on a regional and national scale, where land protection does not occur, the rate of indigenous vegetation loss due to a range of activities, including vegetation clearance and earthworks has not slowed." (1)

Cross reference:

» Issue P11: Earthworks

» General policy on Indigenous biodiversity (Section 5.5 Issue TM2)

P13: Mining and Quarrying

Issue P13: Mining and quarrying can have effects on tāngata whenua values, such as water, landscapes, wāhi tapu and indigenous vegetation.

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

P13.1 To oppose any mining activity in riverbeds and the coastal marine area that is not associated with gravel extraction.

P13.2 To assess mining and quarrying proposals with reference to:

(a) Location of the activity:

- What is the general sensitivity of the site to the proposed activity?

- How well does the proposed activity ‘fit’ with the existing landscape?

- Is there significant indigenous biodiversity on the site, including remnant native bush?

- What waterways, wetlands or waipuna exist on the site?

- Are there sites of significance on or near the site?

- What is the risk of accidental discoveries?

- What is the wider cultural landscape context within which the site is located?

(b) Type of mining/quarrying

- What resource is being extracted, what will it be used for, and is it sustainable?

(c) Avoiding and mitigating adverse effects

- What provisions are in place to address sediment and erosion control?

- What provisions are in place for stormwater management?

- What provisions are in place for waterway protection?

- How will the site be restored once closed?

P13.3 To require all applications for mining and quarrying activities to include:

(a) Quarry management plans for earthworks, erosion and sediment control, waterway protection, on site stormwater treatment and disposal and provisions for visual screening/ barriers that include indigenous vegetation; and

(b) Site rehabilitation plans that include restoration of the site using indigenous species.

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

Quarrying involves the extraction of aggregate such as crushed rock, rotten rock, gravels or sand from the land. These materials are used in both rural and urban construction, infrastructure and agricultural activities.

The effects of quarrying on values of importance to tāngata whenua are dependent on the location and scale of the activity and the nature of the receiving environment. Policy P13.2 is intended to provide a framework for assessing quarrying proposals against the issues of importance to tāngata whenua.

The extraction of gravels from riverbeds in addressed in Section 5.3 Issue WM12.

Cross reference:

» General policy on offshore exploration and mining (Section 5.6, Issue TAN9)

» Issue P18: Fracking

P14: Commercial forestry

Issue P14: Commercial forestry can have significant effects on tāngata whenua values, particularly:

(a) Loss of cultural and natural landscape values;

(b) Establishment and spread of wilding trees;

(c) Reduction in stream and river flows that are already at low flows;

(d) Physical modification and damage to waterways;

(e) Contamination and sedimentation of waterways;

(f) Damage or destruction of significant sites;

(g) Loss of indigenous biodiversity values, including mahinga kai; and

(h) Encroachment on, and loss of, indigenous remnants, including in gullies and along streams.

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

P14.1 To promote the establishment of native forestry operations in the takiwā alongside other commercial operations.

P14.2 To assess proposals for commercial forestry and activities associated with the replanting of existing plantations with particular regard to:

(a) Species – what species will be planted and what is the level of risk of wilding establishment and spread?

(b) Scale of planting – to what extent will the activity dominate the landscape?

(c) Location and visibility – to what extent will the activity encroach (physical and visual) on sites and landscape features of importance to tāngata whenua?

(d) Cumulative impacts – what forestry activities already exist in the area?

(e) Availability of water – how will the activity affect the availability of water in the catchment?

(f) Waterways – what are the potential effects on the beds and margins of waterways during planting and harvesting activity?

(g) Mahinga kai – will the activity compromise mahinga kai species or habitat, including fish passage?

(h) Existing vegetation cover – will the activity involve the clearance of native vegetation?

(i) Wilding tree control – what provisions are proposed to control wilding trees?

(j) Sediment and erosion control – what provisions are in place to control erosion (post harvest) and avoid sedimentation of waterways?

(k) Future land use – what are the post harvest land use and remediation plans?

Protection mechanisms

P14.3 To require that commercial forestry activities do not occur in areas identified by tāngata whenua as sensitive for cultural or ecological reasons, including:

(a) Significant cultural landscapes, natural landscapes and coastal natural character areas;

(b) Margins of high country lakes;

(c) Along waterways in coastal areas;

(d) Naturally dry and water sensitive catchments (to protect flows); and

(e) Areas that are high risk for soil erosion.

P14.4 Where existing commercial plantations are located in areas identified as significant cultural landscapes, natural landscapes or coastal natural character areas, or in water sensitive catchments:

(a) Harvesting should be followed with planting of native species.

P14.5 To oppose the granting of global consents for activities associated with commercial forestry.

P14.6 To use the following mechanisms to protect values of importance to tāngata whenua on commercial forest lands during both planting and harvesting stages:

(a) Tāngata whenua advice and input to planting plans (resourced by the forestry company);

(b) Buffers and set back areas of at least 20 metres from any site of significance identified by tāngata whenua, including wetlands, waterways, waipuna, lakes, or remnant indigenous forest area (e.g. gullies), and these must be recognised during planting and harvesting;

(c) Buffers of at least 20 metres around the outer perimeter of forestry blocks, planted with native species, to provide a refuge for bird and insect species at harvest time, erosion and sedimentation control post harvest, and control the spread of wilding trees (see Issue P15, Policy P15.2);

(d) Access protocols to enable Ngāi Tahu whānui to gain access to commercial forest lands for access to cultural materials and sites;

(e) Ensure that forestry companies are aware that there may be both known (i.e. registered) and unknown (i.e. not discovered) sites of significance, and that these are protected by the Historic Places Act;

(f) Requirement that forestry companies have GPS references for all known sites and that these are marked on operational plans;

(g) Accidental Discovery Protocol, archaeological assessment and cultural monitoring;

(h) Education of contractors and operational staff on how to identify accidental discoveries; and

(i) Stream-side management plans that address the potential effects of machinery and earthworks on the beds and margins of waterbodies with machinery and earthworks.

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

Tāngata whenua are concerned with the effects of forestry on land, water, indigenous biodiversity and landscape values in some areas of the takiwā. If not managed appropriately, plantation forestry can result in soil erosion, sediments and contaminants entering waterways, and the establishment and spread of wilding trees. Plantations can negatively affect catchment water yield as pine trees absorb a significant amount of water, including stormwater that would otherwise contribute to the catchment’s water yield. While the New Zealand Forest Accord 1991 and the Principles for Commercial Plantation Forest Management in New Zealand (agreements between forestry companies and environmental groups) provide guidelines for environmental protection, they currently do not offer a sufficient level of protection to meet tāngata whenua objectives for the protection of cultural and ecological values.

In 1999, Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu developed a project to identify the non-commercial values within commercial forest lands - those features, sites or values within the forest lands which have historical, spiritual or cultural significance to Ngāi Tahu. The project also identified a number of protection mechanisms to enable the planting and harvesting of commercial forests while protecting tāngata whenua values and interests at specific sites. Policy 14.6 reflects the outcomes of this project.

Forestry is identified as an issue of local significance in several catchments in the takiwā, including Rakahuri (Section 6.3), Waimakariri (Section 6.4), Southern Bays (Section 6.9), and Te Roto o Wairewa (Section 6.10).

Cross reference:

» Issue P15: Wilding trees

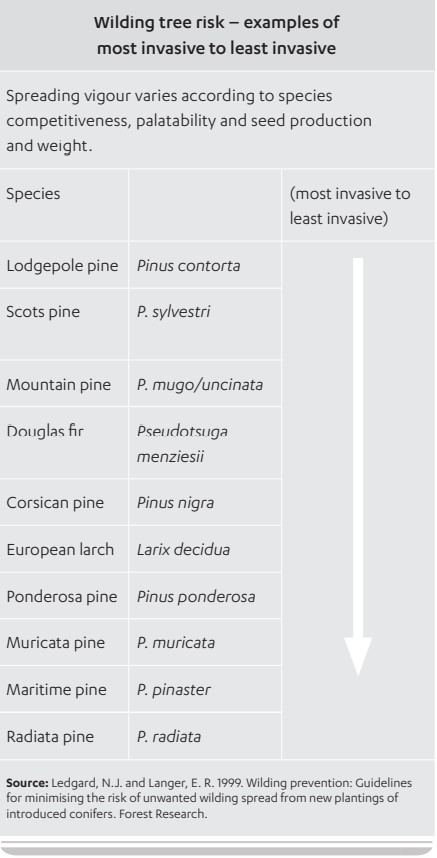

P15: Wilding Trees

Issue P15: Eradication of wilding trees in high country and foothill regions.

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

P15.1 To prioritise the eradication of wilding trees from those areas with recent invasions (i.e. tackle the ones that have yet to become large scale invasions).

P15.2 To require effective district and regional policy to prevent the establishment and control the spread of wilding trees, including:

(a) Prohibiting the planting of high risk species in plantations, shelter belts or amenity plantings;

(b) Requiring buffers or margins of low risk species (less spread prone conifers or native tree species) around all forestry blocks; and

(c) Requiring control of wilding seedlings, including keeping property boundaries clean.

P15.3 To support regional risk assessment mapping as a tool to:

(a) Identify current and potential seed sources of wilding trees;

(b) Assess spread risk, based on seed sources, existing vegetation cover and land management; and

(c) Set priorities for control operations and monitoring.

P15.4 For those areas already highly infested:

(a) Focus on defining the area and controlling further spread; (b) Address elimination; and

(c) Consider whether the area of wilding trees could be used as a nursery crop and underplant with natives (e.g. restore a beech forest).

P15.5 Ngāi Tahu must have the ability to identify and recommend areas of high cultural and historic value, alongside areas of high environmental value identified by Environment Canterbury for wilding tree control.

P15.6 Economics must not have precedence over the environmental costs of wilding trees (e.g. Douglas Fir may be immensely economically beneficial, but it is becoming a wilding/invasive tree in its own right).

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

Wilding trees are introduced conifer species that are self-sown or growing wild (i.e. naturally regenerating). Wilding pines invade quickly, out-competing native vegetation and resulting in significant visual and ecological changes to the landscape. The Waimakariri river catchment is one of the worst affected areas in Canterbury (See Section 6.4 Issue WAI9).

Pinus contorta, or lodgepole pine, is one of the most invasive of conifer species. It is included in the Canterbury Regional Pest Management Strategy (2011) as a pest species. It seeds earlier and therefore can spread more vigorously than other species. Of little commercial value, Pinus contorta is less likely to be managed appropriately and this increases the risk of wilding tree establishment and spread.

Cross reference:

» P14: Commercial forestry

P16: Transport

Issue P16: The protection of sites of significance and indigenous biodiversity, and the potential for erosion and sedimentation, are issues of importance to tāngata whenua with regard to land transport infrastructure.

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

Consultation

P16.1 To require that engagement with Papatipu Rūnanga occurs at the early planning stages (i.e. designation stage) of major transport proposals, This may or may not include:

(a) Cultural impact assessment (CIA) reports; and

(b) Archaeological assessments.

P16.2 Where a transport proposal may affect Māori land:

(a) Papatipu Rūnanga to be notified; and

(b) Consultation must occur with the owners of that land.

Assessments of effects

P16.3 To assess the potential risk of transport related proposals (at any stage) on tāngata whenua values on the basis of the following:

(a) Purpose of the proposal - how consistent is the purpose of the proposal with the objectives set out in this IMP (e.g. stormwater, indigenous biodiversity)?

(b) Sites of significance - proximity to sites of cultural significance, including marae, wāhi tapu, silent files and archaeological sites;

(c) Protection of waterways - what measures are proposed to avoid the modification of waterways, the discharge of contaminants and sediment to water?

(d) Indigenous biodiversity - what are the potential effects on existing indigenous biodiversity and what are the opportunities to enhance indigenous biodiversity values?

Protection of tāngata whenua values

P16.4 To require that the development and construction of transport infrastructure avoid the following sites and areas of cultural significance:

(a) Sites identified by tāngata whenua as wāhi tapu;

(b) Some sites identified by tāngata whenua as wāhi taonga; and

(c) Māori land, unless agreed to by owners.

P16.5 To support the development of tribal Heritage Risk Model or Heritage Alert Layers to protect wāhi tapu, wāhi taonga and archaeological sites located within the State Highway Network in Canterbury.

P16.6 To continue to recognise the Accidental Discovery Protocol (2003) for the Transit New Zealand Canterbury region, agreed to by Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu, the Historic Places Trust, and Transit New Zealand.

P16.7 To support improved transport network infrastructure and services to support the development aspirations of Ngāi Tahu communities, such as those at Tuahiwi and Rāpaki.

P16.8 To support sustainable transport measures in urban design and development, including public transport, pedestrian walkways, and cycle ways.

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

Land transport infrastructure includes the state highways and other roads, rail network, cyclist and pedestrian provisions and public transport.

The construction of new roads and other transport infrastructure involves earthworks and therefore the potential risk to wāhi tapu and wāhi taonga must be considered (Issue P11 Earthworks). Sediment and contaminant discharges associated with earthworks and stormwater are also important issues, as these discharges can affect water quality in local waterways. Land transport infrastructure can also provide opportunities for the enhancement of cultural values, through initiatives such as roadside plantings using indigenous species.

A good working relationship between Ngāi Tahu and the NZ Transport Agency is fundamental to protecting sites of significance, as are appropriate tools and processes for engagement with tāngata whenua and assessments of effects on values of importance.

Cross reference:

» Issue P6: Stormwater

» General policy on cultural landscapes (Section 5.8 Issue CL1)

» General policy on wāhi tapu me wāhi taonga (Section 5.8 Issue CL3)

» General policy on indigenous biodiversity (Section 5.5Issues TM2 and TM3)

Information resource:

» Hullen, J (2007) Christchurch Southern Motorway Project. Cultural Impact Assessment report: An assessment of effects on Ngāi Tūāhuriri, Ngāi Te Ruahikihiki and Ngāi Tahu Values

P17: Energy

Issue P17: Ngāi Tahu have a particular interest in energy generation, distribution and use.

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

Consultation

P17.1 Ngāi Tahu must have a strategic and influential role in decisions about energy extraction and generation in the region, as a Treaty partner with specific rights and interests in resources used for energy generation, particularly water.

P17.2 To continue to engage with the energy sector and build constructive and enduring relationships.

P17.3 To require that the energy sector engage with Ngāi Tahu at the concept development stage, rather than at the resource consent stage and to support the use of Cultural Impact Assessment (CIA) reports to assess potential and actual effects of proposals on Ngāi Tahu values.

P17.4 To require that local authorities develop and implement effective policies requiring the use of renewable energy and energy-saving measures in residential, commercial, industrial and other developments.

P17.5 To support in principle the use of wind and solar energy generation in the region (see Section 5.7, Issue TAW1).

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

Ngāi Tahu have an interest in the extraction, generation, distribution and use of energy in the takiwā. An issue of particular significance is the use of water to generate energy, given the potential for damming, diversion and storage to have effects on the relationship of tāngata whenua to ancestral rivers, and fundamental questions about competition for water resources and commercial use.

Ngāi Tahu are also interested in finding ways to reduce energy consumption. The debate on energy is often centered on extraction and production rather than the need to reduce consumption, particularly non-renewable fossil fuels. Alternative sources of energy generation such as wind (Section 5.7, Issue TAW1) and solar are highlighted in various sections of this plan as a means to reduce our energy footprint.

Meaningful and enduring relationships with the energy industry based on a mutual understanding of each other’s values and interests associated with water and other resources is fundamental to addressing current and future energy issues in the takiwā.

Cross reference:

» Issue P4: Subdivision and development

» Issue P18: Fracking

» General policy on regional water infrastructure (Section 5.3 Issue WM9)

» General policy on wind farms (Section 5.7, Issue TAW1)

P18: Fracking

Issue P18: Tāngata whenua have significant concerns about the use of fracking for oil and gas exploration, including:

(a) Adequacy of the regulatory environment;

(b) Potential to contaminate ground and surface water;

(c) The volume of water used;

(d) The disposal of waste; and

(e) Potential to generate earthquakes.

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

P18.1 To oppose any application for mineral exploration or extraction in the takiwā that uses fracking as a method to fracture rock for gas release.

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

Fracking is the hydraulic fracturing of geological formations to release hydrocarbons. Water, with chemicals added to it, is discharged at high pressure into wells to crack the rock and get oil and gas out. Fracking is seen as a means to extract those oil and gas resources that are deemed too expensive or difficult to extract by conventional means.

Tāngata whenua oppose fracking in its entirety. The environmental and cultural impacts of fracking are deemed too significant in a region that is currently trying to manage an increasing demand on water resources, contaminated waterways and geological shakeups. The risk of long term contamination of land and water resources is considered too high. Further, accessing non-renewable resources that are otherwise too difficult or expensive to extract is contrary to finding ways to reduce energy consumption and promoting alternative energy sources.

P19: Overseas Investment and Purchase of Land

Issue P19: Overseas investments and purchases of property and effects on the relationship of tāngata whenua with ancestral lands, water, sites, wāhi tapu and other taonga

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

P19.1 In the context of the Overseas Investment Commission, Papatipu Rūnanga support the retention of New Zealand land in New Zealand ownership.

P19.2 To require that the Overseas Investment Commission formally recognise and provide for Ngāi Tahu interests for all overseas investment applications, in particular:

(a) Ngāi Tahu historical, cultural, traditional and spiritual relationship with the land;

(b) The protection of particular values associated with the land; and

(c) Ngāi Tahu access to sites and places of cultural importance.

P19.3 To support the following methods to enable the Overseas Investment Commission to recognise and provide for Ngāi Tahu values:

(a) Early engagement with Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu and Papatipu Rūnanga;

(b) Preparation of Cultural Value Reports (as used for Tenure Review Process) to identify values, risk and desired outcomes;